TopThe Landing-Place in Britain of Gaius Julius Cæsar IV

This community website is regularly updated so click to refresh the page to see the latest content

Gaius Julius Cæsar was the name of several members of the gens Julia in ancient Rome. It was the full name (tria nomina) of Gaius Julius Cæsar IV (12 July 100 B.C. - 15 March 44 B.C.), 'the dictator', son of Gaius Julius Cæsar III 'the Elder', grandson of Gaius Julius Cæsar II (prætor urbanus) and great grandson of Gaius Julius Cæsar I 'the historian'.

Chiaramonti Cæsar Tusculum Bust The Tusculum Portrait, also called the Tusculum Bust, is one of the two accepted portraits of Julius Gaius Cæsar IV, alongside the Chiaramonti Cæsar, which were made before the beginning of the Roman Empire. According to several scholars, the Tusculum Bust is the only extant portrait of Julius Gaius Cæsar IV made during his lifetime. Being one of the copies of the bronze original, the bust is dated to 50-40 B.C. and is housed in the permanent collection of the Museo d'Antichitá in Turin, Italy. Made of fine-grained marble, the bust measures 1ft 1in (33 cm) in height. According to Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, The Lives of the Twelve Cæsars Chapter XLV

"It is said that he was tall, of a fair complexion, round limbed, rather full faced, with eyes black and piercing; and that he enjoyed excellent health, except towards the close of his life, when he was subject to sudden fainting-fits, and disturbance in his sleep. He was likewise twice seized with the falling sickness while engaged in active service. He was so nice in the care of his person, that he not only kept the hair of his head closely cut and had his face smoothly shaved, but even caused the hair on other parts of the body to be plucked out by the roots, a practice for which some persons rallied (railed ?) him. His baldness gave him much uneasiness, having often found himself on that account exposed to the jibes of his enemies. He therefore used to bring forward the hair from the crown of his head; and of all the honours conferred upon him by the senate and people, there was none which he either accepted or used with greater pleasure, than the right of wearing constantly a laurel crown. It is said that he was particular in his dress. For he used the Latus Clavus with fringes about the wrists, and always had it girded about him, but rather loosely. This circumstance gave origin to the expression of Sylla, who often advised the nobles to beware of 'the ill-girt boy'."

The following articles, drawings and extracts cover the period from 58 B.C. to 2019 A.D. (Gaius Julius Cæsar IV) and are listed here in date order of publication (oldest first):

- "Commentarii de Bello Gallico", (Commentaries on the Gallic War) 58-49 B.C., Gaius Julius Cæsar, Books IV and V

- "De Vita Cæsarum" (The Lives of the Twelve Cæsars) A.D. 121, Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus at paragraphs 25, 47 and 58

- "Roman History" Cassius Dio, AD 164-235, Books 39 and 40

- "Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation", Bede, A.D. 731, Book I, Chapter II

- "General History: Roman Kent" in The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 1 (Edward Hasted, Canterbury, 1797) pages 13 to 44

- "The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent" (1800) Edward Hasted Volume 10 at page 1 and Volume 9 at page 549

- The South Eastern Gazette Tuesday 4 January 1853 at page 6

- The South Eastern Gazette Tuesday 18 March 1856 at page 5

- "On Cæsar's Landing-Place in Britain" (1858) R.C. Hussey, Archæologia Cantiana, volume 1 at pages 94 to 110

- "The Landing-Place of Julius Cæsar in Britain" (1860) Archæologia Cantiana, volume 3 pages 1 to 17

- The South Eastern Gazette Tuesday 6 November 1860 at page 3

- "Archaeologia or miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity" (1863) Society of Antiquaries of London at pages 277 to 314

- "Ramsgate Scientific Association" (1873) The South Eastern Gazette, Tuesday 25 November at page 5

- "The Landing-Place of Julius Cæsar" (1873) The South Eastern Gazette, Tuesday 2 December at page 6

- "Deal and its Environs" (1900) Archæologia Cantiana, volume 24 pages 108 & 109

- "A Peep into the Past: Britain in the Days of Cæsar" (1904) The South Eastern Gazette, Tuesday 16 February at page 3

- "The Coming of Rome: Britain before the Conquest" (1979) John Wacher at pages 1 to 11 and 51 to 53

- "Richborough Environs Project, Kent"Aerial Survey Report Series AER/12/2002 at page 9

- "Julius Cæsar's First Landing in Britain" History Today, Volume 55 Issue 8 August 2005

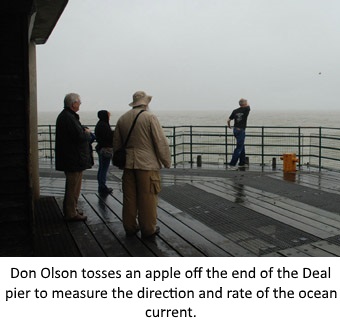

- "Tide and time: re-dating Cæsar's invasion of Britain" Texas State University, Thursday 25 June 2008

- "Doubt over date for Brit invasion" BBC, Tuesday 1 July 2008

- "Hidden Roman coastline unearthed by archaeologists in Kent" The Telegraph, 2 October 2008

- "First evidence of Julius Cæsar's invasion of Britain discovered in Kent" The Independent, 29 November 2017

- "Revealed, where Julius Cæsar veni vidi, vici'd: Landing site for invasions of Britain in 55 and 54 B.C. pinpointed for the first time" Daily Mail, 29 November 2017

- "Caesar's invasion route of Britain is revealed by remains of 'marching camps' that show he landed at Dover and swept through Essex" Daily Mail, 5 May 2019

- "Julius Cæsar's invasions of Britain" Heritage Daily, 24 May 2021

"Commentarii de Bello Gallico", (Commentaries on the Gallic War) 58-49 B.C., Gaius Julius Cæsar, Books IV and V

Map of Gaul showing all the tribes and cities mentioned in De Bello GallicoDe Bello Gallico, Gaius Julius Cæsar, Book IV, paragraphs 20 to 29 (first invasion of Britain in 55 B.C.):

- During the short part of summer which remained, Cæsar, although in these countries, as all Gaul lies toward the north, the winters are early, nevertheless resolved to proceed into Britain, because he discovered that in almost all the wars with the Gauls succours had been furnished to our enemy from that country; and even if the time of year should be insufficient for carrying on the war, yet he thought it would be of great service to him if he only entered the island, and saw into the character of the people, and got knowledge of their localities, harbours, and landing-places, all which were for the most part unknown to the Gauls. For neither does any one except merchants generally go thither, nor even to them was any portion of it known, except the sea-coast and those parts which are opposite to Gaul. Therefore, after having called up to him the merchants from all parts, he could learn neither what was the size of the island, nor what or how numerous were the nations which inhabited it, nor what system of war they followed, nor what customs they used, nor what harbours were convenient for a great number of large ships.

- He sends before him Caius Volusenus with a ship of war, to acquire a knowledge of these particulars before he in person should make a descent into the island, as he was convinced that this was a judicious measure. He commissioned him to thoroughly examine into all matters, and then return to him as soon as possible. He himself proceeds to the Morini with all his forces. He orders ships from all parts of the neighbouring countries, and the fleet which the preceding summer he had built for the war with the Veneti, to assemble in this place. In the mean time, his purpose having been discovered, and reported to the Britons by merchants, ambassadors come to him from several states of the island, to promise that they will give hostages, and submit to the government of the Roman people. Having given them an audience, he after promising liberally, and exhorting them to continue in that purpose, sends them back to their own country, and dispatches with them Commius, whom, upon subduing the Atrebates, he had created king there, a man whose courage and conduct he esteemed, and who he thought would be faithful to him, and whose influence ranked highly in those countries. He orders him to visit as many states as he could, and persuade them to embrace the protection of the Roman people, and apprize them that he would shortly come thither. Volusenus, having viewed the localities as far as means could be afforded one who dared not leave his ship and trust himself to barbarians, returns to Cæsar on the fifth day, and reports what he had there observed.

- While Cæsar remains in these parts for the purpose of procuring ships, ambassadors come to him from a great portion of the Morini, to plead their excuse respecting their conduct on the late occasion; alleging that it was as men uncivilized, and as those who were unacquainted with our custom, that they had made war upon the Roman people, and promising to perform what he should command. Cæsar, thinking that this had happened fortunately enough for him, because he neither wished to leave an enemy behind him, nor had an opportunity for carrying on a war, by reason of the time of year, nor considered that employment in such trifling matters was to be preferred to his enterprise on Britain, imposes a large number of hostages; and when these were brought, he received them to his protection. Having collected together, and provided about eighty transport ships, as many as he thought necessary for conveying over two legions, he assigned such ships of war as he had besides to the quaestor, his lieutenants, and officers of cavalry. There were in addition to these eighteen ships of burden which were prevented, eight miles from that place, by winds, from being able to reach the same port. These he distributed among the horse; the rest of the army, he delivered to Q. Titurius Sabinus and L. Aurunculeius Cotta, his lieutenants, to lead into the territories of the Menapii and those cantons of the Morini from which ambassadors had not come to him. He ordered P. Sulpicius Rufus, his lieutenant, to hold possession of the harbour, with such a garrison as he thought sufficient.

- These matters being arranged, finding the weather favourable for his voyage, he set sail about the third watch, and ordered the horse to march forward to the further port, and there embark and follow him. As this was performed rather tardily by them, he himself reached Britain with the first squadron of ships, about the fourth hour of the day, and there saw the forces of the enemy drawn up in arms on all the hills. The nature of the place was this: the sea was confined by mountains so close to it that a dart could be thrown from their summit upon the shore. Considering this by no means a fit place for disembarking, he remained at anchor till the ninth hour, for the other ships to arrive there. Having in the mean time assembled the lieutenants and military tribunes, he told them both what he had learned from Volusenus, and what he wished to be done; and enjoined them (as the principle of military matters, and especially as maritime affairs, which have a precipitate and uncertain action, required) that all things should be performed by them at a nod and at the instant. Having dismissed them, meeting both with wind and tide favourable at the same time, the signal being given and the anchor weighed, he advanced about seven miles from that place, and stationed his fleet over against an open and level shore.

Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Gaius Julius Cæsar, Book IV, at paragraph 23 (first invasion of Britain in 55 B.C.):

"… he set sail about the third watch … he himself reached Britain … about the fourth hour of the day …"

The Romans divided the night into four watches consisting of three hours each:

- the first (evening) commenced at six and continued until nine;

- the second (midnight) from nine to twelve;

- the third (cock-crowing) from twelve to three; and

- the fourth (morning) from three to six.

The four watches are named in Mark 13:35: "Watch ye therefore: for ye know not when the master of the house cometh, at even, or at midnight, or at the cock-crowing, or in the morning."

It is probable that the term watch was given to each of these divisions from the practice of placing sentinels around the camp in time of war, or in cities, to watch or guard the camp or city; and that they were at first relieved three times in the night, but under the Romans four times.

- But the barbarians, upon perceiving the design of the Romans, sent forward their cavalry and charioteers, a class of warriors of whom it is their practice to make great use in their battles, and following with the rest of their forces, endeavoured to prevent our men landing. In this was the greatest difficulty, for the following reasons, namely, because our ships, on account of their great size, could be stationed only in deep water; and our soldiers, in places unknown to them, with their hands embarrassed, oppressed with a large and heavy weight of armour, had at the same time to leap from the ships, stand amid the waves, and encounter the enemy; whereas they, either on dry ground, or advancing a little way into the water, free in all their limbs in places thoroughly known to them, could confidently throw their weapons and spur on their horses, which were accustomed to this kind of service. Dismayed by these circumstances and altogether untrained in this mode of battle, our men did not all exert the same vigour and eagerness which they had been wont to exert in engagements on dry ground.

- When Cæsar observed this, he ordered the ships of war, the appearance of which was somewhat strange to the barbarians and the motion more ready for service, to be withdrawn a little from the transport vessels, and to be propelled by their oars, and be stationed toward the open flank of the enemy, and the enemy to be beaten off and driven away, with slings, arrows, and engines: which plan was of great service to our men; for the barbarians being startled by the form of our ships and the motions of our oars and the nature of our engines, which was strange to them, stopped, and shortly after retreated a little. And while our men were hesitating whether they should advance to the shore, chiefly on account of the depth of the sea, he who carried the eagle of the tenth legion, after supplicating the gods that the matter might turn out favourably to the legion, exclaimed, "Leap, fellow soldiers, unless you wish to betray your eagle to the enemy. I, for my part, will perform my duty to the commonwealth and my general." When he had said this with a loud voice, he leaped from the ship and proceeded to bear the eagle toward the enemy. Then our men, exhorting one another that so great a disgrace should not be incurred, all leaped from the ship. When those in the nearest vessels saw them, they speedily followed and approached the enemy.

- The battle was maintained vigorously on both sides. Our men, however, as they could neither keep their ranks, nor get firm footing, nor follow their standards, and as one from one ship and another from another assembled around whatever standards they met, were thrown into great confusion. But the enemy, who were acquainted with all the shallows, when from the shore they saw any coming from a ship one by one, spurred on their horses, and attacked them while embarrassed; many surrounded a few, others threw their weapons upon our collected forces on their exposed flank. When Cæsar observed this, he ordered the boats of the ships of war and the spy sloops to be filled with soldiers, and sent them up to the succour of those whom he had observed in distress. Our men, as soon as they made good their footing on dry ground, and all their comrades had joined them, made an attack upon the enemy, and put them to flight, but could not pursue them very far, because the horse had not been able to maintain their course at sea and reach the island. This alone was wanting to Cæsar's accustomed success.

- The enemy being thus vanquished in battle, as soon as they recovered after their flight, instantly sent ambassadors to Cæsar to negotiate about peace. They promised to give hostages and perform what he should command. Together with these ambassadors came Commius the Altrebatian, who, as I have above said, had been sent by Cæsar into Britain. Him they had seized upon when leaving his ship, although in the character of ambassador he bore the general's commission to them, and thrown into chains: then after the battle was fought, they sent him back, and in suing for peace cast the blame of that act upon the common people, and entreated that it might be pardoned on account of their indiscretion. Cæsar, complaining, that after they had sued for peace, and had voluntarily sent ambassadors into the continent for that purpose, they had made war without a reason, said that he would pardon their indiscretion, and imposed hostages, a part of whom they gave immediately; the rest they said they would give in a few days, since they were sent for from remote places. In the mean time they ordered their people to return to the country parts, and the chiefs assembled from all quarter, and proceeded to surrender themselves and their states to Cæsar.

- A peace being established by these proceedings four days after we had come into Britain, the eighteen ships, to which reference has been made above, and which conveyed the cavalry, set sail from the upper port with a gentle gale, when, however, they were approaching Britain and were seen from the camp, so great a storm suddenly arose that none of them could maintain their course at sea; and some were taken back to the same port from which they had started; others, to their great danger, were driven to the lower part of the island, nearer to the west; which, however, after having cast anchor, as they were getting filled with water, put out to sea through necessity in a stormy night, and made for the continent.

- It happened that night to be full moon, which usually occasions very high tides in that ocean; and that circumstance was unknown to our men. Thus, at the same time, the tide began to fill the ships of war which Cæsar had provided to convey over his army, and which he had drawn up on the strand; and the storm began to dash the ships of burden which were riding at anchor against each other; nor was any means afforded our men of either managing them or of rendering any service. A great many ships having been wrecked, inasmuch as the rest, having lost their cables, anchors, and other tackling, were unfit for sailing, a great confusion, as would necessarily happen, arose throughout the army; for there were no other ships in which they could be conveyed back, and all things which are of service in repairing vessels were wanting, and, corn for the winter had not been provided in those places, because it was understood by all that they would certainly winter in Gaul.

Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Gaius Julius Cæsar, Book V, paragraphs 7 to 11 (second invasion of Britain in 54 B.C.):

- Having learned this fact, Cæsar, because he had conferred so much honour upon the Aeduan state, determined that Dumnorix should be restrained and deterred by whatever means he could; and that, because he perceived his insane designs to be proceeding further and further, care should be taken lest he might be able to injure him and the commonwealth. Therefore, having stayed about twenty-five days in that place, because the north wind, which usually blows a great part of every season, prevented the voyage, he exerted himself to keep Dumnorix in his allegiance and nevertheless learn all his measures: having at length met with favourable weather, he orders the foot soldiers and the horse to embark in the ships. But, while the minds of all were occupied, Dumnorix began to take his departure from the camp homeward with the cavalry of the Aedui, Cæsar being ignorant of it. Cæsar, on this matter being reported to him, ceasing from his expedition and deferring all other affairs, sends a great part of the cavalry to pursue him, and commands that he be brought back; he orders that if he use violence and do not submit, that he be slain; considering that Dumnorix would do nothing as a rational man while he himself was absent, since he had disregarded his command even when present. He, however, when recalled, began to resist and defend himself with his hand, and implore the support of his people, often exclaiming that "he was free and the subject of a free state." They surround and kill the man as they had been commanded; but the Aeduan horsemen all return to Cæsar.

- When these things were done and Labienus left on the continent with three legions and 2,000 horse, to defend the harbours and provide corn, and discover what was going on in Gaul, and take measures according to the occasion and according to the circumstance; he himself, with five legions and a number of horse, equal to that which he was leaving on the continent, set sail at sun-set, and though for a time borne forward by a gentle south-west wind, he did not maintain his course, in consequence of the wind dying away about midnight, and being carried on too far by the tide, when the sun rose, espied Britain passed on his left. Then, again, following the change of tide, he urged on with the oars that he might make that part of the island in which he had discovered the preceding summer, that there was the best landing-place, and in this affair the spirit of our soldiers was very much to be extolled; for they with the transports and heavy ships, the labour of rowing not being for a moment discontinued, equalled the speed of the ships of war. All the ships reached Britain nearly at mid-day; nor was there seen a single enemy in that place, but, as Cæsar afterward found from some prisoners, though large bodies of troops had assembled there, yet being alarmed by the great number of our ships, more than eight hundred of which, including the ships of the preceding year, and those private vessels which each had built for his own convenience, had appeared at one time, they had quitted the coast and concealed themselves among the higher points.

- Cæsar, having disembarked his army and chosen a convenient place for the camp, when he discovered from the prisoners in what part the forces of the enemy had lodged themselves, having left ten cohorts and 300 horse at the sea, to be a guard to the ships, hastens to the enemy, at the third watch, fearing the less for the ships, for this reason because he was leaving them fastened at anchor upon an even and open shore; and he placed Q. Atrius over the guard of the ships. He himself, having advanced by night about twelve miles, espied the forces of the enemy. They, advancing to the river with their cavalry and chariots from the higher ground, began to annoy our men and give battle. Being repulsed by our cavalry, they concealed themselves in woods, as they had secured a place admirably fortified by nature and by art, which, as it seemed, they had before prepared on account of a civil war; for all entrances to it were shut up by a great number of felled trees. They themselves rushed out of the woods to fight here and there, and prevented our men from entering their fortifications. But the soldiers of the seventh legion, having formed a testudo and thrown up a rampart against the fortification, took the place and drove them out of the woods, receiving only a few wounds. But Cæsar forbade his men to pursue them in their flight any great distance; both because he was ignorant of the nature of the ground, and because, as a great part of the day was spent, he wished time to be left for the fortification of the camp.

- The next day, early in the morning, he sent both foot-soldiers and horse in three divisions on an expedition to pursue those who had fled. These having advanced a little way, when already the rear of the enemy was in sight, some horse came to Cæsar from Quintus Atrius, to report that the preceding night, a very great storm having arisen, almost all the ships were dashed to pieces and cast upon the shore, because neither the anchors and cables could resist, nor could the sailors and pilots sustain the violence of the storm; and thus great damage was received by that collision of the ships.

- These things being known to him, Cæsar orders the legions and cavalry to be recalled and to cease from their march; he himself returns to the ships: he sees clearly before him almost the same things which he had heard of from the messengers and by letter, so that, about forty ships being lost, the remainder seemed capable of being repaired with much labour. Therefore he selects workmen from the legions, and orders others to be sent for from the continent; he writes to Labienus to build as many ships as he could with those legions which were with him. He himself, though the matter was one of great difficulty and labour, yet thought it to be most expedient for all the ships to be brought up on shore and joined with the camp by one fortification. In these matters he employed about ten days, the labour of the soldiers being unremitting even during the hours of night. The ships having been brought up on shore and the camp strongly fortified, he left the same forces as he did before as a guard for the ships; he sets out in person for the same place that he had returned from. When he had come thither, greater forces of the Britons had already assembled at that place, the chief command and management of the war having been entrusted to Cassivellaunus, whose territories a river, which is called the Thames, separates, from the maritime states at about eighty miles from the sea. At an earlier period perpetual wars had taken place between him and the other states; but, greatly alarmed by our arrival, the Britons had placed him over the whole war and the conduct of it.

Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Gaius Julius Cæsar, Book V, paragraph 14:

"The most civilized of all these nations are they who inhabit Kent, which is entirely a maritime district, nor do they differ much from the Gallic customs. Most of the inland inhabitants do not sow corn, but live on milk and flesh, and are clad with skins. All the Britons, indeed, dye themselves with woad, which occasions a bluish colour, and thereby have a more terrible appearance in fight. They wear their hair long, and have every part of their body shaved except their head and upper lip. Ten and even twelve have wives common to them, and particularly brothers among brothers, and parents among their children; but if there be any issue by these wives, they are reputed to be the children of those by whom respectively each was first espoused when a virgin."

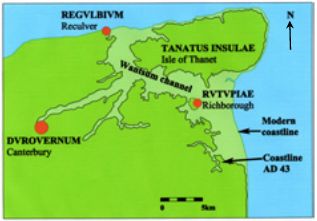

Eastern Kent A.D. 43 showing old and new coastline

adapted from "The Cantiaci" by Alec Detsicas (page 34, figure 7)

"De Vita Cæsarum", (The Lives of the Twelve Cæsars), A.D. 121, Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus at paragraphs 25, 47 and 58

Gaius Julius Cæsar's two invasions of Britain are referred to in just 3 paragraphs of De vita Cæsarum (The Lives of the Twelve Cæsars) (A.D. 121) by Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus. Paragraphs 25, 47 and 58 below are taken from Robert Graves' 1965 translation:

25. Briefly, his nine years' governorship produced the following results. He reduced to the form of a province the whole of Gaul enclosed by the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Cevennes, the Rhine, and the Rhone - about 640,000 square miles - except for certain allied states which had given him useful support; and exacted an annual tribute of 400,000 gold pieces. Cæsar was the first Roman to build a military bridge across the Rhine and cause the Germans on the farther bank heavy losses. He also invaded Britain, a hitherto unknown country, and defeated the natives, from whom he exacted a large sum of money as well as hostages for future good behaviour. He met with only three serious reverses: in Britain, when his fleet was all but destroyed by a gale; in Gaul, when one of his legions was routed at Gergovia among the Auvergne mountains; and on the German frontier, when his generals Titurius and Aurunculeius were ambushed and killed.

47. Fresh-water pearls seem to have been the lure that prompted his invasion of Britain; he would sometimes weigh them in the palm of his hand to judge their value, and was also a keen collector of gems, carvings, statues, and Old Masters. So high were the prices he paid for slaves of good character and attainments that he became ashamed of his extravagance and would not allow the sums to be entered in his accounts.

58. It is a disputable point which was the more remarkable when he went to war: his caution or his daring. He never exposed his army to ambushes, but made careful reconnaissances; and refrained from crossing over into Britain until he had collected reliable information (from Gaius Volusenus) about the harbours there, the best course to steer, and the navigational risks. On the other hand, when news reached him that his camp in Germany was being besieged, he disguised himself as a Gaul and picked his way through the enemy outposts to take command on the spot. He ferried his troops across the Adriatic from Brindisi to Dyrrhachium in the winter season, running the blockade of Pompey's fleet. And one night, when Mark Antony had delayed the supply of reinforcements, despite repeated pleas, Cæsar muffled his head with a cloak and secretly put to sea in a small boat, alone and incognito; forced the helmsman to steer into the teeth of a gale, and narrowly escaped shipwreck.

"Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation", Bede, 731 A.D., Book I, Chapter II

CHAPTER II

Caius Julius Cæsar, the first Roman that came into Britain

BRITAIN had never been visited by the Romans, and was, indeed, entirely unknown to them before the time of Caius Julius Cæsar, who, in the year 693 after the building of Rome, but the sixtieth year before the incarnation of our Lord, was consul with Lucius Bibulus, and afterwards while he made war upon the Germans and the Gauls, which were divided only by the river Rhine, came into the province of the Morini, from whence is the nearest and shortest passage into Britain. Here, having provided about eighty ships of burden and vessels with oars, he sailed over into Britain; where, being first roughly handled in a battle, and then meeting with a violent storm, he lost a considerable part of his fleet, no small number of soldiers, and almost all his horses. Returning into Gaul, he put his legions into winter quarters, and gave orders for building six hundred sail of both sorts. With these he again passed over early in spring into Britain, but, whilst he was marching with a large army towards the enemy, the ships, riding at anchor, were, by a tempest either dashed one against another, or driven upon the sands and wrecked. Forty of them perished, the rest were, with much difficulty, repaired. Cæsar's cavalry was, at the first charge, defeated by the Britons, and Labienus, the tribune, slain. In the second engagement, he, with great hazard to his men, put the Britons to flight. Thence he proceeded to the river Thames, where an immense multitude of the enemy had posted themselves on the farthest side of the river, under the command of Cassibellaun, and fenced the bank of the river and almost all the ford under water with sharp stakes: the remains of these are to be seen to this day, apparently about the thickness of a man's thigh, and being cased with lead, remain fixed immovably in the bottom of the river. This, being perceived and avoided by the Romans, the barbarians not able to stand the shock of the legions, hid themselves in the woods, whence they grievously galled the Romans with repeated sallies. In the meantime, the strong city of Trinovantum, with its commander Androgeus, surrendered to Cæsar, giving him forty hostages. Many other cities, following their example, made a treaty with the Romans. By their assistance, Cæsar at length, with much difficulty, took Cassibellaun's town, situated between two marshes, fortified by the adjacent woods, and plentifully furnished with all necessaries. After this, Cæsar returned into Gaul, but he had no sooner put his legions into winter quarters, than he was suddenly beset and distracted with wars and tumults raised against him on every side.

"General History: Roman Kent" in The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent" (1800) Edward Hasted Volume 1 (Edward Hasted, Canterbury, 1797) pages 13 to 44

Roman Kent

Britain was in the state above-mentioned when Cæsar turned his thoughts to the invasion of it, at which time the Romans were become masters of almost all Europe, the best part of Africa, and the richest countries of Asia. Whilst they were continually adding so many kingdoms to their empire, Britain still preserved its independency, for which it was indebted to its remote situation, more than to its strength. It was considered by the inhabitants of the continent as a separate world, of which (excepting in the maritime parts opposite to it,) they had very little knowledge, and what they had did not excite their desires to extend their dominion over it. Julius Cæsar, during his wars with the Gauls, had taken great umbrage at the supplies which the neighbouring parts of Britain had continually sent to them: at least this was the specious pretence for his leading his forces hither; a pretence frequently made use of by the Romans, to carry their conquests into the most remote countries; though his unbounded ambition was, most probably, the sole motive that urged him to it. It was in the 698th year after the building of Rome, and fifty-five years before the birth of Christ, Cn. Pompey and Marcus Lic. Crassus being then consuls of Rome, that Julius Cæsar resolved to undertake a voyage into Britain, and though the summer was then almost spent, he would by no means delay it; not that he expected the advanced season of the year would permit him to carry on the war, yet he thought it would be of no small use to him, if he only landed and discovered something of the nature of the inhabitants, the country, and its havens. To gain some intelligence, therefore, Cæsar summoned together all the merchants round about, but he could not learn from any of them, either what the size of Britain was, what or how many nations inhabited it, what progress they had made in the art of war, what customs they used, or what number of ships their ports were capable of receiving. This uncertainty made him determine to send out Gaius Volusenus Quadratus with a galley, to make what discoveries he could without danger. In the meantime he himself marched with all his forces into the country of the Morini, now the province of Picardy, from whence the passage into Britain was said to be the shortest, and thither he ordered the shipping from all the neighbouring parts.

The Morini (from the Gaulish morinos 'seaman') were a Belgic tribe of northern Gaul. Cæsar was very interested in that part of the Morini territory, which is where the crossing of the sea to Britannia was "the shortest". The Morini had several harbours of which Portus Itius (generally considered to be either Wissant or Boulogne) was only one.

Whilst these preparations were going forward, the merchants gave notice to the Britons of Cæsar's design, who sent messengers to him, in hopes of diverting him from his purpose, promising to deliver hostages, and to submit themselves to the Roman empire. Cæsar gave them a civil reception, made them liberal promises, and, encouraging them to persist in their resolution, sent them home again.

Along with them he sent Comius, whom he had made king of the Attrebates, in Gaul, a person, whose interest in those parts was accounted very great, and whose fidelity Cæsar had a great opinion of. He commanded Comius to visit as many states as he could, and persuade them to accept an alliance with the Romans, and farther, to tell them, that he would very quickly be over with them in person.

Volusenus, in the meantime, having made what discoveries he could of the country, for he durst not venture himself ashore, after five days cruising, returned, and acquainted Cæsar with all he had seen; who having, in the meantime, got together eighty transports, which he thought sufficient to carry over the foot of his two legions, besides his gallies, and eighteen more transports for the horse, which lay wind-bound at another port, eight miles distant, set sail with the foot about one o'clock in the morning, and left orders for the horse to march to the other port, and to embark there, and follow him as soon as they could.

Cæsar himself, with the foremost of his ships, arrived on the coast of Britain about ten o'clock the same morning, where he saw all the cliffs covered by the enemy in arms, and he observed (what would render the execution of his design most difficult at this place) that, the sea being narrow, and pent in by the hills, the Britons could easily throw their darts from thence upon the shore beneath.

Not thinking this place proper therefore for landing, he came to an anchor, and waited for the rest of his fleet till three in the afternoon; after which, having got both wind and tide for him, he weighed anchor, and sailed about eight miles farther, and then came to a plain and open shore, where he ordered the ships to bring to.

The Britons being apprised of his design, sent their horse and chariots before, and following after with the rest of the army, endeavoured to prevent their landing. Here the Romans laboured under very great difficulties, for their ships, on account of their size, could not lie near the shore, and their soldiers with their hands encumbered and loaded with heavy armour, were obliged to contend, at the same time both with the waves and the enemy, in a place they were unacquainted with; whereas the Britons, either standing upon dry ground, or but a little way in the water, in places with which they were well acquainted, and being free and unincumbered, could boldly cast their darts, and spur their horses forward, which were used to this kind of combat, which disadvantage so discouraged the Romans, who were unused to this way of fighting, that they did not behave themselves with the same spirit that they used to do, in their engagements on dry land.

Cæsar perceiving this, gave orders for the gallies to advance gently before the rest of the fleet, and to row along with their broadsides towards the shore, and then by every kind of missive weapon to drive the enemy away. This piece of conduct was of considerable service to them, for the Britons being terrified, quickly after began to give ground; upon which the soldiers, though at first unwilling, encouraging one another, leaped down into the sea, from the several ships, and pressed forward towards the enemy. The conflict was sharply maintained on both sides; in which the Romans, not being able either to keep their ranks, obtain firm footing, or follow their particular standards, fell into great disorder; whilst the Britons, who were well acquainted with the shallows, spurring their horses forward, assaulted the enemy, incumbered and unprepared to receive them.

Cæsar observing this, caused the boats and pinnaces to be filled with soldiers, and dispatched them to the relief of those who stood in need of it; these charged the Britons, and quickly put them to flight, but could not pursue, as their horse were not then arrived.

The Britons, upon this, as soon as they had escaped beyond the reach of danger, sent messengers to desire peace, promising to deliver hostages for the performance of whatever Cæsar had commanded. He at first upbraided, and then pardoned, their imprudence, and demanded hostages of them; some of which they delivered immediately, and promised to return in a few days, with the rest: in the meantime they dispersed their men, and the chiefs assembled from all parts, and recommended themselves and their states to Cæsar's protection.

Upon the fourth day after Cæsar's arrival in Britain, the transports with the horse, of which mention has been already made, set fail with a gentle gale; but when they were arrived so near as to be within view of the Roman camp, the whole fleet was dispersed by a sudden storm, and afterwards, though with much difficulty, made the best of its way back to the continent.

The same night the moon was at full, and, consequently, it made a spring tide, an observation the Romans were strangers to; so that at the same time both the gallies, which had been drawn on shore, were filled with water, and the ships of burthen, which rode at anchor, were greatly distressed and damaged. Several of them were lost, and the rest were rendered wholly unfit for service, which caused a great consternation throughout their whole army; for they had no other ships to carry them back again, nor any materials to refit their own with; and they knew very well they must of necessity take up their winter quarters in Gaul, as there was no provision of corn against winter made for them here.

As soon as the British chiefs, who had been assembled to perform their agreement with Cæsar, knew of this, and that the Romans were without horses, ships, and provisions, concluding from the smallness of their camp, (which was then narrower than usual, because the legions had left their heavy baggage in Gaul) that their soldiers were but few, they resolved upon a revolt, and to hinder the Romans from foraging, and delay them till winter; imagining that if they could but gain a victory over them, or prevent their return, none would ever dare to make such another attempt; and having entered into a new confederacy, they began by degrees to quit the Roman camp, and privately to enlist their disbanded troops again.

Though Cæsar knew nothing of their design, yet suspecting, from the loss of his shipping, and their delay in the delivery of their hostages, what afterwards really happened, prepared for all events, causing provisions to be brought into his camp every day, and repairing the ships that were least damaged by which means, with the loss of twelve, he made the rest fit for sea again.

Whilst matters were in this situation, the seventh legion, whose turn it was, went out to forage, whilst some of the men were employed in the fields, and others in carrying the corn between them and the camp, the out-guards gave Cæsar notice, that they observed a greater dust than usual, in that part of the country to which the legion went. Upon which, suspecting that the Britons had revolted, he took with him the cohorts that were placed for an advanced guard, and commanded the rest to repair to their arms, and follow him as fast as possible.

He had not marched far before he saw his foragers overcharged by the Britons, and drove into a small compass; for the Britons, knowing there was but one place where the harvest had not been carried in, suspected the Romans would come there, and having hid themselves the night before in the woods, suddenly set upon the soldiers, who had laid down their arms, and were dispersed and busy in reaping the corn, and having killed some of them, they put the rest in disorder, and then surrounded them with their horse and chariots.

Their way of fighting with their chariots was this; first they drove up and down everywhere, and flung their darts about, the very terror and noise of their horses and chariots frequently putting the ranks of the enemy in disorder; and whenever they got in among the ranks of the horse, they alighted, and fought on foot. Their charioteers, in the meantime, drove a little way out of the battle, and placed themselves in such a manner that, if their masters should be overpowered by the numbers of the enemy, they might readily retreat to them. Thus they performed in their battles all the activity of the horse, and the steadiness of the foot, at the same time, and were so expert, by daily use and exercise, that even, when they were going full speed on the side of a steep hill, they could stop their horses and turn, run upon the pole, rest on the harness, and thence throw themselves, with great dexterity, into their chariots again.

The Romans being disordered by this new kind of fight, Cæsar came very opportunely to their assistance; for on his arrival the Britons made a stand, and the Romans began to forget their fears. However, not thinking it advisable to venture an engagement at that time, after remaining on the same spot for a little while, he retreated with his legions to the camp. The badness of the weather, which followed after this for several days successively, kept the Romans in their camp, and the Britons from attempting any thing against them. In the meantime the latter sent messengers to all parts, to give information of the smallness of the Roman army, and to shew how considerable a booty they might obtain, and what a glorious opportunity then offered of making themselves free for ever, if they could but force the enemy's camp; by which means they quickly raised great numbers of horse and foot, and came down to it for that purpose.

Although Cæsar foresaw that the Britons, in case they were routed, would, as they had done before, escape the danger by flight, yet having got thirty horse, which Comius of Arras brought over with him, he drew his legions up in order of battle before the camp, and having engaged the Britons, who were not long able to sustain the attack, put them to flight, and the soldiers pursuing them as far as they could, killed many of them, and burnt all their houses for some distance round.

The very same day, the Britons sent messengers to desire a peace, when Cæsar demanded double the number of hostages he had before to be sent into Gaul, for the autumnal equinox being near he did not think it safe to sail with such weak ships in the winter season; seizing, therefore, the first favourable opportunity of the wind's being fair, he set sail soon after midnight, and arrived safe at the continent. Probably he left this island about the 20th of September, about twenty-five days after his landing, and, as he says, a little before the equinox, which at that time must have been on the the 25th of that month.

This is Cæsar's account of this short expedition, which, however plausible he may have dressed it up in his Commentaries, yet his sudden departure in the night, immediately following the battle, carries with it a strong suspicion of his having been beaten by the Britons. Horace, Tibullus, and Lucan, seem to confirm it, as do Tacitus and Dion Cassius in their histories.

A more modern writer of our own nation, H. Huntingdon, who lived about an hundred years after the Norman conquest, says, that Cæsar was disappointed in his hopes; for on his landing he had a sharper conflict with the Britons than he could have believed, and perceiving that his forces were too few for such an enterprise, and that the enemy was much more powerful than he imagined, he was of necessity compelled to re-embark, and that then, being caught in a storm, he lost the greatest part of his fleet, a great number of his soldiers, and almost all his cavalry; at which, being dismayed, he returned to Gaul, sorely wounded at his disappointment.

Westminster says much the same, as does Bede. Polidore Virgil, an Italian, who is always severe on the English, in his history, tells us, the report was, that Cæsar, being routed by the Britons at the first encounter, fled into Gaul.

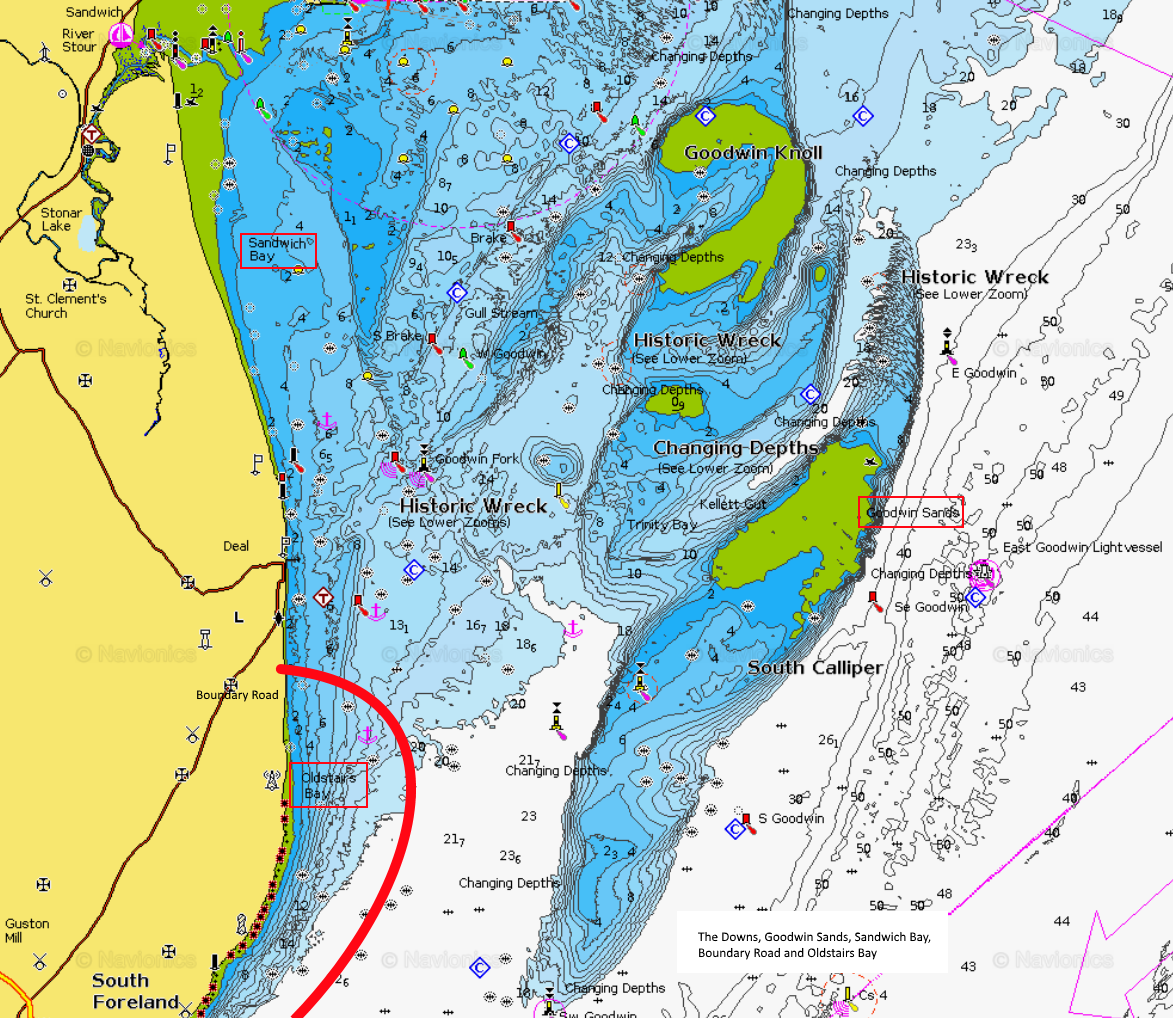

Dr. Halley published a discourse (in Philos. Trans. No. 193) to prove at what time Cæsar landed in Britain, in which he makes it plain, that the cliffs mentioned by Cæsar were those of Dover, and that from the tide, and other circumstances, the Downs was the place where he landed.

In this expedition Cæsar made no advances into the country; the unexpected opposition he met with prevented whatever designs he might have had towards it. Upon the whole, the result of this attempt seems to have been no more than a discovery of the most convenient place of landing and that, if he again attempted the conquest of this country, he stood in need of a much superior force, than what he had then with him.

The Britons, it seems, were not much awed by the Romans; for of all the states into which this island was then divided, two only sent hostages. Provoked at this contempt, Cæsar determined to make a second invasion next year, with a far more powerful fleet and army. For which purpose, when he left his winter quarters in Gaul, as he usually did every year to go into Italy, he gave orders to his lieutenants, who were to command the legions in his absence, that they should build, during the winter, as many ships as they could, and repair the old ones. And at the same time he showed them the manner and form in which he would have them made, directing them to be built something lower than they used to be in the Mediterranean, that the soldiers might both embark and get ashore again with greater ease; and likewise broader than ordinary, as more convenient for the number of horses he intended carrying in them, and to contrive them all for oars, for which the lowness of them would be very proper.

On Cæsar's return to his army, he found that the soldiers, by their unparalleled diligence, had already built six hundred such ships as he had ordered, and twenty-nine gallies, which would be ready to be launched within a few days. Upon which he commanded them all to meet him at the Portus Itius, from whence he knew there was the most convenient passage into Britain, which here was about thirty miles from the continent.

Where this port was has been variously conjectured; Mr. Camden, and Ortelius, suppose it to have been Witson. Cluverius, and after him Somner, Battely, and others, suppose Boulogne to have been the Portus Itius here mentioned by Cæsar. Lambarde, Horsley, and others, join with Dr. Halley in placing it at or somewhere near Calais. The latter of these in his discourse mentioned above, (Phil. Trans. No. 193) founds his opinion on arguments drawn from the navigation of those times, and Cæsar's description of his voyage. He further observes, that Cæsar's distance of the passage from Portus Itius to Britain comes very near the truth, for by an accurate survey, the distance at Calais, from land to land, is twenty-six English miles, or twenty-eight and a half Roman.

From hence he set sail for Britain with five legions, and the same number of horse he had left with Labienus, about sunset, with a gentle southwest wind. About midnight it fell calm, and the fleet being driven by the tide, Cæsar, at day-break, found he had left Britain on the left hand. But the tide turning, they fell to their oars, in order to reach that part of it where they had the year before found the best landing.

Cæsar arrived on the coast of Britain about noon, with his whole fleet, but there was no enemy to be seen; though as he afterwards learned from the prisoners, the inhabitants had been there in vast multitudes, but being terrified at the number of the ships, (which, together with the transports, and other vessels which particular officers had prepared for their own accommodation, amounted to above eight hundred,) they had fled from the shore, and had hid themselves among the hills. Having landed his army without opposition, and chosen a proper place to encamp in, when he had learned from the prisoners where the British forces were posted, about midnight Cæsar marched in quest of them, having left ten cohorts and three hundred horse under the command of Q. Atrius, to guard the ships, which he was the less uneasy for as he left them at anchor on a soft and open shore.

When he had marched about twelve miles he discovered the Britons, who, having advanced with their horse and chariots to the banks of a river, began from a rising ground to oppose the passage of the Romans, and to give them battle; but being repulsed by the Roman cavalry, they retired to a place in the woods, which was fortified both by art and nature, in an extraordinary manner, and which seemed to have been so prepared some time before, on account of their own civil wars. All the passages to it were blocked up by heaps of trees, cut down for that purpose, and the Britons seldom venturing to skirmish out of the woods prevented the Romans from entering their works; but the soldiers of the seventh legion, having cast themselves into a testudo and raised a mount against their works, after having received a few wounds, took the place, and drove them out of the woods; Cæsar however would not permit them to follow the pursuit, because he was unacquainted with the country, and the day being already far spent, he was desirous of employing the rest of it in fortifying his camp.

Various have been the conjectures of our antiquaries concerning this place of the Britons fortified both by art and nature. Horsley thinks it likely that this engagement was on the banks of the river Stour, a little to the north of Durovernum, or Canterbury, in the way towards Sturry, which is about fourteen English miles from the Downs; others well acquainted with this part of Kent, have conjectured it to have been on the banks of the rivulet below Barhamdowns, and that the fortification of the Britons was in the woods behind Kingston, towards Bursted; and the distance as well as the situation of this place, and the continued remains of Roman works about it, almost in a continued line to Deal, add some strength to this conjecture.

Some have placed this encounter below Swerdling downs, three miles north-west from Bursted, and the intrenchment in the woods above the downs behind Heppington, where many remains of intrenchments, &c. are still visible.

Perhaps the engagement was below Barham-down; the fortification near Bursted, as before-mentioned; and the remains above Swerdling, the place to which the Britons retreated after they were put to flight by the Romans, and where Cæsar again found them after he had fortified his camp with their allies under the command of Cassivelaun.

The next morning, having divided his army into three bodies, Cæsar sent both his horse and foot in pursuit of the Britons; soon after which, before the rear of them had got out of sight, some horsemen arrived from Q. Atrius, to acquaint him that the night before there had happened a dreadful storm which had shattered almost all his ships and cast them on the shore, for neither anchors nor cables could hold them, nor could all the skill of the mariners and pilots resist the force of the tempest, so that the fleet, from the great number of shipping lying together, received considerable damage.

Upon this intelligence the Roman general, countermanding his forces, returned himself in person to the fleet, and there found that about forty of his ships were entirely lost, and that the rest of them were so much damaged, as not to be refitted without great trouble and labour. Wherefore, having chosen some workmen for this purpose from among his soldiers, and sent for others from the continent, he wrote to Labienus to build him as many ships as he could with those legions that were left with him; and he himself determined, though it would be an affair that would be attended with great toil and labour, to have his fleet hauled on shore, and to inclose it with his camp, within the same fortification, in the execution of which, the soldiers laboured ten days and nights without intermission, and at this day, upon the shore about Deal, Sandown, and Walmer, there is a long range of heaps of earth, where Camden supposes this ship camp to have been, and which in his time, he says, was called by the people, as he was told, Rome's work. though some have conjectured, and perhaps with some probability, that the place of Cæsar's naval camp was where the town of Deal now stands.

When the shipping being drawn on shore and the camp exceedingly well fortified, Cæsar left the same guard over the fleet as he had before and returned to the place where he had desisted from pursuing the Britons. On his arrival, he found they had assembled their forces there in greater numbers from all parts than when he left the place before. By general consent the chief command and management of the war was intrusted to Cassivelaun whose territories were divided from the maritime states by the river Thames, about eighty miles distant from the sea. There had been before that time continual wars between Cassivelaun and the rest of the states in the island; but the Britons, being terrified on the arrival of the Romans, had conferred the chief direction of affairs on him at so important a conjuncture.

Whilst the Romans were on their march they were briskly attacked by the British horse and chariots, whom they repulsed, with great slaughter, and drove them into the woods; but being too eager in the pursuit, lost some of their own men. Not long after this the Britons made a sudden sally out of the woods, and sharply attacked the advanced guard of the Romans, who little expected them, and were employed in fortifying their camp; upon which Cæsar immediately dispatched the two first cohorts of his legions to their assistance; but the Britons, whilst the soldiers stood amazed at their new way of fighting, boldly broke through the midst of them, and returned again without the loss of a man.

Quintus Laberius Durus was slain in this action but some fresh cohorts coming up the Britons were at last repulsed. This is Cæsar's account; but our historian, Henry of Huntingdon, says that in this engagement Labienus, the tribune, and his battalion, being incompassed by the Britons, were all slain, and Cæsar perceiving the day was lost and that the Britons were to be encountered more by art than strength, determined, before his loss was too great, to save himself by flight; upon which the Britons, pursuing the Romans, killed many of them, and were at last restrained, only by the contiguity of the woods; and Bede goes farther, and tells us, the Britons gained the victory.

This engagement happening in the view of the whole Roman army, they all perceived that the legionary soldiers were not equal to cope with such an enemy, as the weight of their armour would not permit them to pursue, nor durst they go too far from their colours. Neither could their cavalry encounter them without great danger, as the Britons often counterfeited a retreat, and having drawn them from the legions, would leap from their chariots and fight on foot, to a great advantage. For the engagements of the cavalry, whether they retreated or pursued, were attended with one and the same danger. To which may be added, that the Britons never fought in close battalions, but in small parties, at a great distance from one another, each of them having their particular post allotted, whence they received supplies, and the weary were relieved by those who were fresh and untired.

The next day the Britons posted themselves on the hills, at some distance from the Roman camp, appearing but seldom, and with less eagerness to harrass the enemy's horse than the day before. But about noon, when Cæsar had sent out three legions and all the cavalry, under the command of C. Trebonius, to forage, they suddenly rushed on the foragers from all parts, insomuch as to fall in with the legions and their standards. But the Romans returning the attack briskly, drove them back, nor did the cavalry, (who depended on the legions, which followed close after, to sustain them in case of necessity) desist from pursuing the Britons, till they had entirely routed them, great numbers of whom were slain; for the Romans pursued them so close, that they had no opportunity either of rallying, making a stand, or forsaking their chariots.

Upon this rout the British auxiliaries, which had come from all parts, left them; nor did the Britons ever after this engage the Romans with their united forces. From hence Cæsar marched his army to the river Thames, towards the territories of Cassivelaun, which river was fordable only in one place, and that with great difficulty, and on his arrival there, he saw the British forces drawn up in a considerable body on the opposite bank, which was fortified with sharp stakes; they had likewise driven many stakes of the same sort so deep into the bottom of the river, that the tops of them were covered with the water.

Notwithstanding Cæsar had intelligence of this from the prisoners and deserters, yet he ordered his army to pass the river, which they did with such resolution and entrepidity, (though the water took them up to the neck) that the Britons, not being able to sustain their assault, abandoned the bank, and fled.

Cassivelaun, now despairing of success by a battle, disbanded the greatest part of his forces, and contented himself with watching the motions of the Romans, from time to time, and betaking himself to the woods, and other places, inaccessible to the Romans.

In the meantime several states had submitted themselves to Cæsar; and Cassivelaun, to divert him from pursuing his conquests, sent his messengers into Kent, which was then governed by four petty princes; Cingetorix, Carnilius, Taximagulus, and Segonax, whom Cæsar styles Kings, and commanded them to raise what forces they could, and suddenly attack the camp where his ships were laid up; which they did, but were repulsed, with great slaughter, in a sally made by the Romans, who took Cingetorix prisoner, and returned, without any loss, to their trenches.

Upon the news of this defeat Cassivelaun, reflecting on the many losses he had sustained, that his country was laid waste, and that several of the neighbouring states had submitted, sent messengers to Cæsar to treat of a surrender. As the summer was already far spent, Cæsar, who was determined to winter in Gaul to prevent sudden incursions there, readily hearkened to their proposals, demanded hostages, and imposed an annual tribute on the country. Having received the hostages he marched his army back to the seashore, where, finding his ships refitted, he caused them to be launched, and as he had a great number of captives, and some of his ships had been lost in the storm, he resolved to transport his army in two voyages. But as most of the ships which were sent back from Gaul, after they had landed the soldiers that were first carried over, and of those which Labienus had built for him, were driven back by contrary winds, Cæsar, after having long expected them in vain, lest the winter should prevent his voyage, the equinox being near at hand, crowded his soldiers closer than he designed and taking the opportunity of an extraordinary calm, set sail about ten o'clock at night and arrived safe with his whole fleet at the continent by break of day.

It is conjectured, that this second expedition of Cæsar's was in May, and that he returned to Gaul about the middle of September; for, in a letter to Cicero, from Britain, dated September the 1st, he says, he was come to the sea side in order to embark.

Such is the account given by Cæsar of his two expeditions into Britain, who, in penning his Commentaries seems to have framed the whole much to his own advantage. Indeed, no one can read the particulars of these expeditions in them without being sensible that some circumstances must have been omitted for, in some parts, he is scarce consistent with himself, and that whatever was not to his honour, he has passed over in silence, as a proof of which, let us consider Cæsar's design in passing over hither, and attacking the Britons, and the events of it.

He tells us, that he made a descent, with two legions only, in an enemy's country, in the sight of an army, formidable for number, bravery, and peculiar method of fighting, and afterwards in a battle put their united forces to flight. That on his landing, with a much larger force, the second time, he drove the Britons from their advantageous post on the banks of a river, and afterwards from their strong fortification in the woods; that he then routed the British army and their auxiliaries, which had been assembled from all parts of the island; and, what is more wonderful, he passed the Thames at a ford, which was guarded by a numerous army, stuck full of sharp stakes, and so deep as to take the soldiers up to their chins. Such continued scenes of good fortune, it would be imagined, would have secured him success in the design and resolution with which he set sail from Gaul, of conquering Britain, and reducing it to a Roman province, as Dion Cassius positively asserts. Yet, notwithstanding his gaining such victories over the Britons everywhere; his passing the Thames in spite of every obstacle, his vanquishing and routing Cassivelaun, and obliging him to disband most of his forces, in despair of being able to cope with him; his becoming master of the capital of that prince; and the Britons submitting and suing for peace: notwithstanding all these advantages, he was content with ordering Mandubratius to be restored, in the room of Cassivelaun, to the kingdom of the Trinobantes; which command was never executed; for on Cassivelaun's making his submission to Cæsar, he restored him again to his favour, only imposing an easy tribute on him, and then quickly, without fortifying any one place, or leaving any troops in the island, he set sail again for the continent.

So trivial a satisfaction, instead of the conquest of Britain, evidently shows, that the success acquired by Cæsar, in these expeditions, came far short of the idea he endeavours to give us of it. It serves to confirm the testimony of Lucan, who taxes him with turning his back to the Britons; of Dion Cassius, who says, the Roman infantry were entirely routed in a battle by them, and that Cæsar retired from thence without effecting any thing; and of Tacitus, who writes that Cæsar rather showed the Romans the way to Britain, than put them in possession of it; and who in another place makes one of the Britons say that their ancestors had driven out Julius Cæsar from this island.

Whatever promises the Britons had made to Cæsar, in order to get rid of him, they troubled themselves little about the performance of them; and the civil wars which ensued among the Romans were, in great measure, the cause of their neglect of Britain, which continued a long while after peace was restored, as Tacitus elegantly expresses in these words:

"Next follow the civil wars, and the arms of the princes turned against the common-wealth; and hence Britain was long forgot, even in peace."

This neglect of Britain continued till the reign of Claudius, near the space of a whole century, as all the Roman historians acknowledge; during which time the inhabitants of it lived at their own disposal; and, as Dion says, were governed by their own kings. Augustus, indeed, twice made a show of compelling the Britons to fulfil their promises made to his predecessor; and Horace has paid Augustus a compliment on this occasion in more than one of his odes; but the British princes, by courting his friendship by presents and artful addresses, found means to persuade him to give over his design; and Cunobeline, who is said to have succeeded Tenuantius, the successor of Cassivelaun, even caused coins to be stamped after the manner of the Romans; some of which are still to be seen in the cabinets of the curious, having the word Tascia on their reverse, signifying, according to our antiquaries, tribute; for the payment of which it is concluded this money was designed; for though brass and iron rings of a certain weight served, as Cæsar informs us, for their current coin, yet the Romans exacted their tribute in gold and silver, of which latter metal are these coins.

Caligula, the successor of Tiberius, formed a design against Britain, but never put it in execution, which Tacitus ascribes to his instability and the ill success of his vast enterprises in Germany; and Suetonius tells us, that he did no more than receive Adminius, (called also by our writers Guiderius) the son of Cunobeline, who surrendered himself to that emperor with the few men he had with him, having been expelled from his own country by his father. Indeed he made a kind of mock expedition with his army as far as the sea shore opposite to Britain; but being informed the Britons were prepared to receive him, instead of pursuing his design, he ordered his soldiers to fill their helmets with shells, which he called the spoils of the conquered ocean; and then sending his vainglorious letters to the senate, implying the conquest of Britain, he soon followed them to Rome himself.

The Britons may be said to have continued hitherto free from the Roman yoke; but in the reign of Claudius, the successor of Caligula, a great part of the island was brought under subjection to Rome, and the rest by degrees under the succeeding emperors.

In the time of the emperor Claudius, Cunobeline being dead, his two sons, Togodumnus and Caractacus, reigned in Britain in his stead. In their reign, one Bericus - who he was is not known - being driven out of the island for attempting to raise a sedition, fled with those of his party to Rome, and being highly provoked against his countrymen, persuaded the emperor to invade Britain.

On the other hand, the Britons, resenting the emperor's receiving the fugitives, and his refusing to deliver them up, denied the tribute he then demanded of them, and prohibited all commerce with the Romans.

As Claudius wanted only a pretence for the war, he was not sorry they afforded him one so plausible; he was then in his third consulate, and was ambitious of atchieving something that might entitle him to a triumph; therefore he made choice of Britain for his province, and gave orders to Plautius, then Prætor in Gaul, to transport those legions he had with him into Britain, and begin the expedition, whilst he was preparing to follow him, if there should be occasion.

But the Roman soldiers, perhaps, remembering the rough reception the Britons had formerly given to Julius Cæsar, and being, as they said, unwilling to make war beyond the end of the world, at first refused to follow him or obey his commands. However, they were at last prevailed on to embark; and putting to sea in three different parties, lest their landing should be hindered, they made towards Britain, and landed without opposition; for the Britons having been informed of a mutiny in the Roman army, did not expect so sudden an alteration, and had, therefore, made no preparations to oppose them.

It is generally supposed that the emperor sent Plautius into Britain in his third consulate, which fixes it in the year 43; as soon as he had landed he seems to have been very desirous of coming to a battle as soon as possible; but the Britons did all they could to avoid it, and kept themselves in small parties behind their morasses and among their hills in hopes of tiring out the enemy with skirmishes and delays till winter, when they imagined Plautius would go and winter in Gaul, as Julius Cæsar had before.

This resolution much disconcerted the Roman general, who, notwithstanding these difficulties, found means first to attack Caractacus, and afterwards Togodumnus, and defeated them both. He then reduced part of the Dobuni, whence he marched on in quest of the Britons, whom he found carelessly encamped on the farther bank of a river - thought by some to have been the Severn - imagining the Romans could not pass it without a bridge; but Plautius sending over the Germans, who were used to pass the most rapid streams in their armour, they fell upon the astonished Britons, who were forced, after a most obstinate resistance, to betake themselves to flight.

From hence the Britons betook themselves to the Thames, towards the mouth of it, and being acquainted with the nature of the places which were firm and fordable, passed easily; whereas the enemy, in pursuing them, ran great hazards. But the Germans, having swam over the river, and others getting over by a bridge higher up, the Britons were surrounded on all sides, and great numbers of them slain. And the Romans, pursuing too eagerly, fell among the bogs and morasses, and lost great numbers of their own men. Upon this indifferent success, and because the Britons were so far from being daunted at the death of Togodumnus, (who had been slain in one of these battles) that they made preparations with greater fury to revenge it, Plautius fearing the worst, drew back his forces, and taking care to secure the conquests he had already made, sent to Rome to the emperor Claudius to come to his assistance, as he was ordered to do, if his affairs should be in a dangerous situation.

It is plain, from Dion Cassius' account of this expedition, that Plautius waited for the emperor on the south, or Kentish side of the Thames. From his fear of the preparations and fury of the Britons, it is most likely he chose himself an advantageous situation for this purpose, capable of containing his forces, and which he, no doubt strongly entrenched and fortified. It has been thought by many, that the place of his encampment was where those large remains of a Roman camp and entrenchment are still to be seen on Kestondown, near Bromley. Indeed, its nearness to the Thames, as well as its size, strength, and many other circumstances, induce one to think it could hardly be made for any other purpose.

The emperor Claudius no sooner received this news than he set out from Rome with a mighty equipage; and, to strike the more terror, he brought with him several elephants; having pursued his journey, partly by land and partly by sea, till he came to the ocean, he sailed over, and landed in Britain, and immediately marched to join Plautius, who still waited for him near the Thames.

Having taken upon himself the chief command, the whole army passed that river, and in a set battle gave the Britons a signal overthrow. After this he took Camulodunum; supposed by some to have been Maldon; by others Colchester; and by Dr. Gale, Walden, the royal seat of Cunobeline, and a great number of prisoners in it; many by force, and others by surrender.

From the mention Suetonius makes of Claudius's expedition hither, it is insinuated, his conquest in Britain cost no blood. Bede, we may suppose, was of the same opinion, as in his account of it he even copies Suetonius's words: but Dion Cassius, from whom we have the most particular description of this war, gives the above very different account of it.

Whichever the fact was, part of Britain being thus subdued, Claudius disarmed the inhabitants, and appointed Plautius to govern them, and ordered him to subdue those who remained as yet unconquered. To such as had submitted, he generously forgave the confiscation of their estates, which obliged them to such a degree, that they erected a temple to him, and paid him divine honors. The emperor, having staid in Britain about sixteen days, set out from hence on his return to Rome, having sent before him the news of his victories. And though he had conquered but a very small part of this island, yet, on his arrival at Rome, he was rewarded with a triumph, and many other honors, the same as had been decreed to other conquerors, after they had reduced whole kingdoms.

After this, the several governors of Britain, sent over by the Romans, had various success against the Britons; one while the Romans through fear of them taking care not to provoke them by any act of hostility, giving to their cowardly inaction the specious name of peace, and at another time maintaining their conquests, and reducing several warlike states to their empire.

In this situation Britain remained till the celebrated Cneius Julius Agricola was sent to command in it, in the reign of the emperor Vespasian, in the year 78; who not only, by his bravery, extended the Roman empire through Wales and the farthest part of Scotland; but by his prudent management, reconciled the inhabitants to the Roman government; by which means the Britons began to live more contented, and in a state of peace under the Romans; a state which, through the neglect and connivance of former governors, had been, till then, no less dreadful than that of war. For the purpose, he employed his winters here in measures extremely advantageous to the empire; so that the people, wild and dispersed over the country, might, by a taste of pleasures, be reconciled to inactivity and repose, he encouraged them privately, and publicly assisted them to build temples, houses, and places of public resort. He took care to have the sons of their chiefs educated in the liberal sciences, preferring their genius to that of their neighbours, the Gauls; and such was his success, that those who had lately scorned to learn the Roman language, seemed now fond of its elegancies.

From that time many of the Britons began to assume the Roman apparel, and the use of the gown grew frequent among them. Thus, by degrees, they proceeded to the charms and allurements of vice and effeminacy, in their galleries, baths, entertainments, and other kinds of luxury; all which were, as Tacitus judiciously observes, by the inexperienced, styled politeness, though in reality they were only baits of slavery.

Agricola having spent eight years in Britain, ordered the admiral of his fleet to sail round it; which he happily accomplished, and returned, with great reputatation, to the port whence he had departed, and thence proved Britain to be, as it was long thought before, an island.

Though Britain was thus, after so many struggles and contests, entirely reduced, yet the Romans did not long continue masters of it, at least, in Caledonia; for what Agricola won, was, on his being recalled soon after, lost by Domitian, in whose reign the farther, or northern, parts of Britain were left to the natives of them, the Romans contenting themselves with the hither, or southern, part which was reduced to a complete province, not governed by consular or proconsular deputies, but accounted præsidal, and appropriated to the emperors, as being annexed to the empire, after the division of provinces by Augustus, and having proprætors of its own.

The Romans had continued conflicts after this with the northern inhabitants of Britain, the Scots and the Picts. The first mention made of the former infesting this island, is in the year 360. They landed first from Ireland, as the Picts had done before from Scandinavia. These conflicts were attended with various success. At length, in order to restrain these people, and to prevent their making incursions into their provinces, they caused several walls at different times to be built across from sea to sea, which separated at the same time that it defended the provincial part of Britain, in the possession of the Romans, from the northern part, in the hands of the barbarians.